Crystal’s recent reflections on visiting Tuol Sleng have had me thinking about my own experience. I lived in Cambodia for almost three years before I visited Tuol Sleng. I saw Kang Kek Iew (Comrade Duch) in person before I set foot in the place where he committed his most horrible crimes. This will be a longer post and will deal with disturbing material.

When I first moved to Cambodia in 2006, I made the conscious decision to do no research beforehand on the history of Cambodia or the Khmer Rouge. The only historical reading I did was included in the required country guide. I should note that this was very unusual for me – I seek out and devour research material on anything I’m involved with. This departure from my normal process was due to my learning experience with Việt Nam in University.

I participated in several classes on and two cross cultural trips to Việt Nam* through a partnership between Bluffton University and An Giang University. I was especially fortunate because Bluffton was at the time hosting three Professors from Việt Nam. It was an excellent program – ambitious, meaningful, academic, personal, comprehensive. It awoke something new in me – a desire to experience for myself rather than absorb vicariously through research.

*Of note – I visited a border village in An Giang province, Việt Nam that had been attacked by the Khmer Rouge. This was also the first time that, across the border, I saw Cambodia – little did I know then that I would be living there in a few years.

After graduating, I followed the advice of my pastor/mentor Joyce Shutt and signed up for a three year term with Mennonite Central Committee. In my first interview I said that I would go anywhere and they said, “We’re putting together a team to start a rural field office in Cambodia.”

I had culture and language training as part of my in-country orientation but I count it a blessing that Mennonite Central Committee allowed me to go into the countryside without exposing me to Tuol Sleng. It was valuable, to me, to walk alongside the people of Cambodia and learn their story from them rather than starting my time with the greatest darkness in their history. I think that if I had started with Tuol Sleng the darkness there would have defined everything else about my experience.

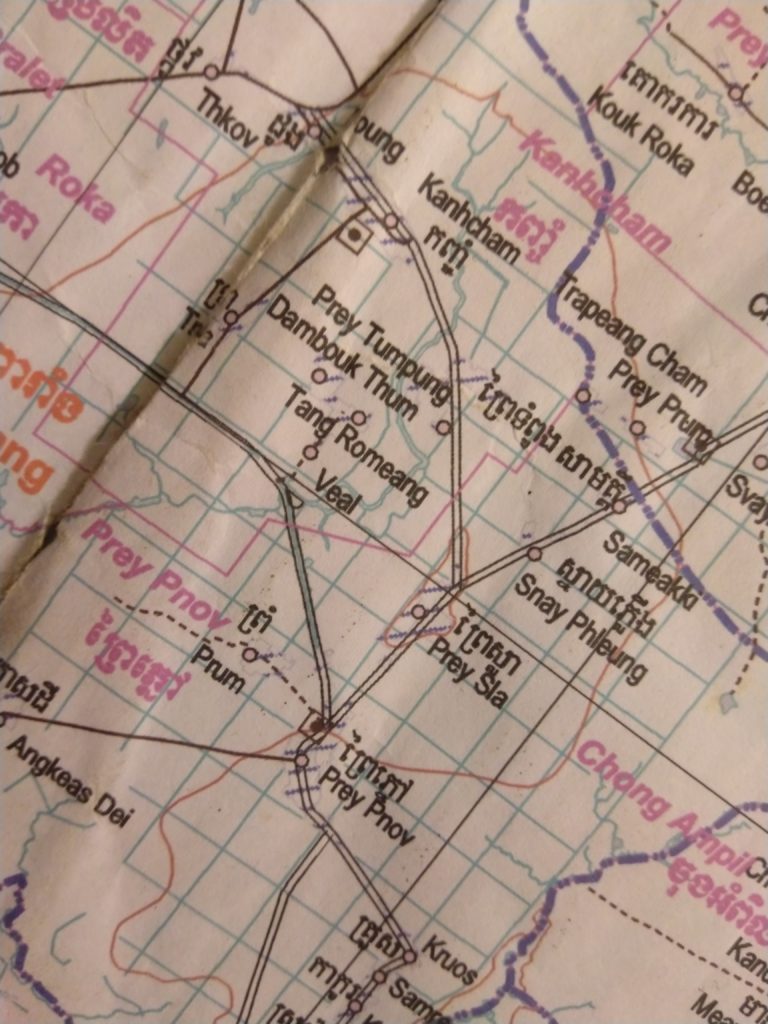

I spent my first year in Prey Veng province slowly learning about Cambodia through the people I met there. Very slowly. I found people surprisingly eager to talk about the Khmer Rouge – villagers often brought it up out of the blue – but my limited Khmer language skills prevented me from gleaning more than the surface details from most of these conversations. I remember that sometimes younger relatives were surprised when their elders opened up to me about the Khmer Rouge, voicing that, “They never talked to me about any of this.” I think there was something about my status as an outsider that made it safe to open up to me.

There were signs of the province’s traumatic history everywhere. Some were physical like old abandoned concrete buildings, untended mounds among the fields that marked mass graves, and villagers with severe scars or missing limbs. Other signs were psychic – the mentally ill mumbling incoherently as they wandered the streets, the casual cruelty towards animals and minorities, and neglected memorials to the dead scattered throughout the province. I’m still trying to understand what it means to live in a context where everyone over the age of 30 (now 40) could be diagnosed with PTSD. And what does it mean for the younger generations, who were spared the horrors of the Khmer Rouge, but whose parents and extended families suffered from untreated trauma?

Early on I learned the most about the Khmer Rouge from my language teacher, Samang Uong. He also shared a great deal of local history with me – going back to the ancient Funan/Nokor Phnom civilization – that I’ll talk about more in future posts.

Samang took me to the killing fields in his homeland district of Ba Phnom and told me what it was like living there under the Khmer Rouge. Unlike the Choeung Ek killing fields located outside of Phnom Penh, the memorial in Ba Phnom was in a state of disrepair and ruin. No tourists came here. There was a large quarry nearby slowly eating away at one of the mountains (Phnom is Khmer for mountain) and the constant rumble of heavy machinery added to the sense that this was not a sacred place. But it felt like a spiritual place despite the memorial falling apart and the mining nearby. The locals believe that the area is haunted and, even visiting at noon, I could feel why. There was a spiritual pressure in the air and a sense of wrongness.

This photo was taken in April, 2008.

Samang told me many stories about life under the Khmer Rouge. Before the war he had been living at a monastery in Phnom Penh while attending school – his father was a well respected traditional poet. Samang joined the air force under Lol Nol. He may have been drafted, I didn’t think to ask at the time. After his plane was shot down shortly before the fall of Phnom Penh, he stripped off his military uniform and pretended to be an uneducated cyclo driver. The Khmer Rouge were going to relocate him from Phnom Penh to a different province but he ran away to his home village of Ba Phnom in Prey Veng province. He told me about several times when he almost died during those years.

Samang was sent to catch fish for the village by the Khmer Rouge. It was cold and he was bit by mosquitoes. Later, another fisherman asked him to keep his fishing hooks but Samang refused saying, “I cannot be responsible for them. Keep them on the hut roof.” The fishing hooks vanished and the other fisherman blamed Samang, reporting him to the higher ups. They wanted to kill Samang for the loss of the fishing hooks but his commune leader intervened because Samang was a very hard worker. Samang told me that he always tried to work as hard as possible while causing no trouble so that he would not be killed. He was considered one of the best workers at digging irrigation canals and said that being a “single, strong, and tactful worker” is what saved his life.

One day Samang found a can of condensed milk in the fields and shared it with the other villagers. This was reported to the higher ups and he was brought before the village for trial. He was accused of stealing the condensed milk. He told me that he said the following in his defense, “If I was a thief, why would I share?” and then swore that if he were a thief that he would kill himself. Again the commune leader supported Samang because he was a hard worker.

In 1978, the villagers in Prey Veng were forced to do even more irrigation canal digging on starvation rations. Samang tried to work harder than anyone else without complaining so that he would not be killed. He said that many villagers were killed for complaining. One day he collapsed while digging an irrigation canal due to starvation and exhaustion. A friend risked his own life by carrying Samang back to the village at the end of the day. Samang did not know it at the time but in May of 1978 Pol Pot initiated a purge of the eastern zone because he felt that the people there had “Khmer bodies but Vietnamese minds.” It’s estimated that approximately 100,000 people were killed during this purge and workloads were increased dramatically to bring out the “true Khmer”.

In 1979, the Khmer Rouge lined up the single men and the single women in Samang’s village in two rows. Samang was then married to the single woman across from him – it’s not in my notes but I think Samang told me there were twenty couples married in this way on that day. This arbitrary method of arranged marriage was standardized across Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge.

Another man I knew told me about the part he played in the Lol Nol regime. I’ll refer to him as Om* – I didn’t get his permission to name him so I want to respect his anonymity.

*The honorific for a individual older than my parents but younger than my grandparents.

Om told me that in the late 1960s he had been flown to a camp in the Philippines by the US Military and trained on how to overthrow the monarchy. I didn’t know enough history to ask him at the time but in retrospect I wish I had clarified if he had been a member of the Khmer Serei. He did tell me that he remained, despite everything that had happened over the decades since, firmly antimonarchist and didn’t regret taking part in the coup that overthrew King Norodom Sihanouk. Highly educated and a Lol Nol officer, he miraculously survived the Khmer Rouge by fleeing to his home province of Prey Veng where he feigned illiteracy during the Khmer Rouge regime. If Om is still alive I plan to meet with him and get his permission to share more of his story.

A memorable encounter occurred after I had been in a moto accident during a visit to a rural primary school and – bruised and a bit bloodied – was slowly heading home after dark. I had to stop for gasoline at a stand in a small rural village. As a child poured gasoline from a glass bottle into my moto, an elderly woman with a krama wrapped around her head approached me. She shook a fist at me and shouted, “Don’t you know what Pol Pot did? Don’t you know what the Khmer Rouge did? My family was killed!” It is extremely unusual in Khmer culture to address a stranger of unknown social status in this way. In response, I bowed respectfully and responded with, “Please pardon me, old lady*. I am sorry.” Her demeanor abruptly shifted and she patted me on the back with the blood red grin of a betel nut chewer, “Oh! This is a polite westerner. You are a good respectful westerner.” I initially thought that she was mad because I was an American and that she thought the US was responsible for what had happened – but that wasn’t the case. We talked for a few minutes before I headed home, wanting to get back to bandage my wounds and patch up the moto. In retrospect, I wish that I had been in a better shape that night and had stayed longer to talk with her.

*The honorific I used was Yey; which is reserved for women who are older than my grandmother.

One of my friends in Phnom Penh was Amara who, at the time, worked in Finance at the Mennonite Central Committee office. She shared with me the heartbreaking story of how her mother was killed by the Khmer Rouge while taking a taxi. This occurred several years after the Vietnamese Counteroffensive removed the Khmer Rouge from power and while they were waging guerrilla warfare in the countryside. Their horror didn’t end in 1979 – in fact, they were recognized by the United Nations as the official government of Cambodia until 1993 and were active in the countryside up until 1999.

As my Khmer language improved I was able to understand more of what the people of Prey Veng were telling me about the Khmer Rouge. Most of the time they were telling me how they had suffered, how their loved ones had been killed, and about the brutal manual labor they had been forced to do. One survivor explained to me that Cambodians hate potatoes because it reminds them of starvation under the Khmer Rouge when they secretly hunted for root vegetables and ate them raw just to survive. Most of the time if Cambodians were caught foraging for food the Khmer Rouge would beat them, cut off their fingers, or kill them outright.

During my second year I started to read about Cambodia. I’ll touch on some highlights here but visit the reading list page for more. I started with firsthand accounts by Cambodian authors first.

The first two books that I read were by Norodom Sihanouk. Prince, Father of Independence, Filmmaker, King, Composer, Prime Minister – Norodom Sihanouk is the single most influential figure in recent Cambodian history. I won’t write more here because Cambodia recently passed a lèse-majesté law and I don’t want to mistakenly appear to be speaking ill of the royal family. I will say that Norodom Sihanouk is one of the most fascinating historical figures that I’ve come across. His two books are My War with the CIA and War and Hope: The Case for Cambodia. Both are out of print but definitely worth reading (back to back) for anyone who wants a deeper understanding of Cambodian history.

Crossing Three Wildernesses is the firsthand account of the Khmer Rouge years that I most highly recommend. The author, U Sam Oeur, was a highly educated poet who destroyed his manuscripts and feigned illiteracy for four years in order to survive under the Khmer Rouge. His account captures details and nuances that other authors, many of whom were children at the time, miss.

Eventually I moved on to reading books on Cambodia written by international authors. Sideshow by William Shawcross outlined my country’s role – which Om had alluded to – in overthrowing the monarchy in the late 1960s.

In 2008, the Khmer Rouge Tribunal took Kang Kek Iew (Comrade Duch) to Choeung Ek as part of an “investigative reenactment”. This event was when I remember the people of Prey Veng beginning to talk publicly with one another about the Khmer Rouge. It was reported in Cambodian media that Duch wept and prayed during the visit. He also admitted that he was responsible and asked for forgiveness. I distinctly remember something a Prey Veng local said, “Duch thinks that by becoming Christian he will be forgiven. But the Khmer people will never forgive him! It doesn’t matter what religion he chooses. He cannot escape karma.”

On June 22, 2009 I attended a day of hearings on the operation of Tuol Sleng at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal. Duch was on the witness stand testifying as the head of Toul Sleng. I’ll share a few of my handwritten notes from this.

Prosecutor: Did Duch annotate this list?

Duch: Yes. That is my handwriting.

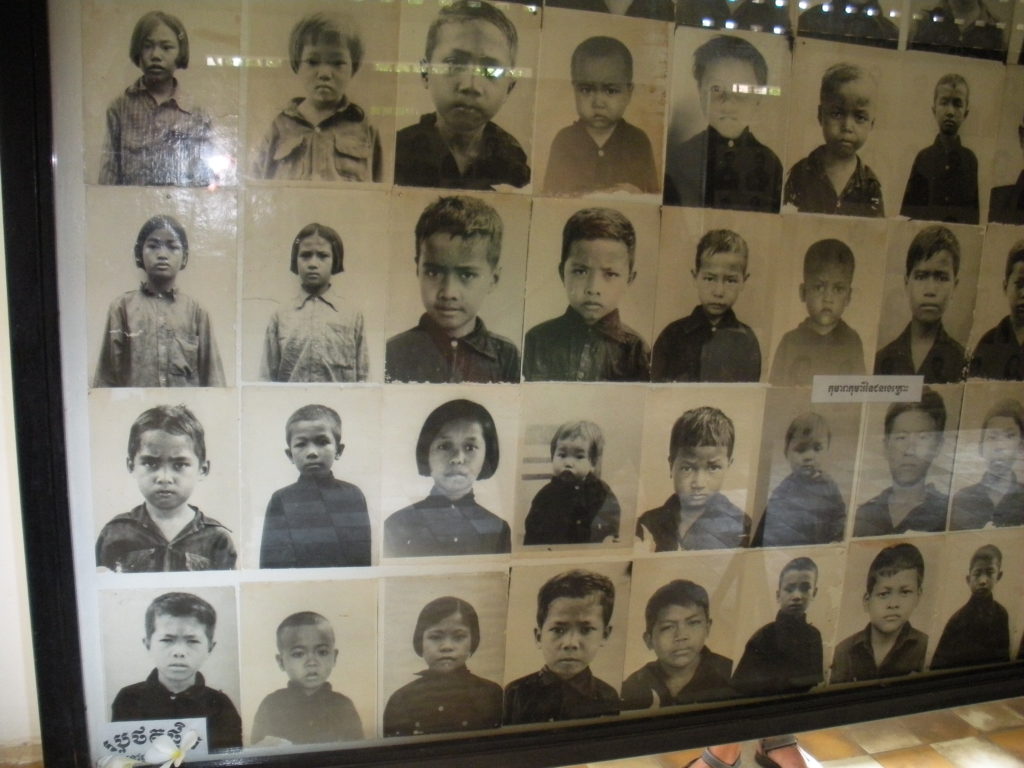

Prosecutor: 17 children. Did you annotate, “Smash them to pieces?”

Duch: It was my instructions.

Duch: Everyone sent to S21 was smashed*. This task was assigned to Ho, then Peang. Normally prisoners sent to S21 had to be smashed. There was an order not to release or allow anyone to escape.

*I wrote down what the translator interpreted but Duch clearly said សម្លាប់ which is normally translated as “kill” not “smash”. I never learned the reason for this, whether it was an error or a more literal translation?

Duch: S21 was an execution center. It was my responsibility but I did not do it myself. I did not want to kill anyone with my own hands*.

*The Prosecutor questioned this several times but Duch answered repeatedly that he ordered that people be killed and did not physically do it himself. It reminded me of Pontius Pilate believing that washing his hands somehow absolved him of signing off on murder.

The Khmer Rouge Tribunal determined that 18,133 people had been tortured and executed at S21 under Duch’s command. On July 26, 2010 the Khmer Rouge Tribunal convicted Duch of crimes against humanity and sentenced him to life imprisonment (the most severe sentence they were permitted to make under their U.N. charter).

In August 2009, Mennonite Central Committee hosted a regional retreat in Phnom Penh. Staff and volunteers gathered from Việt Nam and Laos. MCC Cambodia staff Chylong shared his story of living under the Khmer Rouge and regional staff shared their stories from those years. One of the scheduled activities was visiting Tuol Sleng as a group.

At that time S21 was in a state of disrepair and neglect. It was crowded with tourists – many of whom dealt with the horror by talking loudly and laughing nervously. Despite this, walking into Tuol Sleng was a hallowed experience for me. Like at the killing fields at Ba Pnhom, I felt something spiritual at S21 but rather than a pressure here there was a vacuum. S21 held a tremendous sense of loss. Lost hope. Lost dreams. Lost life.

The photos were familiar to me. The faces looked like people I knew. The emotions on them ranged from defiance to despair to confusion. Many were just blank. They were all tortured and executed. Only 12 of the prisoners who entered S21 survived. Some of the photos were of Khmer Rouge members who had broken a rule or otherwise fallen out of grace – they were convicted of treason and sent to S21 during purges. I couldn’t pick them out. They were all Khmer. The Khmer Rouge did this to their own people knowing that they were their own people.

Norodom Sihanouk had dreamed of great things in the 1950s when he invested heavily in the Cambodian education system to the point that it rivaled Singapore’s. The students who attended Chao Ponhea Yat High School had hopes and dreams. Even the Khmer Rouge started with a dream of what they believed would be a better society. But all of that idealism failed. Chao Ponhea Yat High School was transformed into S21 and what had been known as “the land of smiles” became known as the land of the killing fields.

I don’t know how I would have processed it if I had visited S21 earlier. Faced with such devastating darkness I might have raised my mental defenses by compartmentalizing or rationalizing. When I visited Dachau in Germany I walked out with fury in my heart and “never again” on my lips. I thought I “knew” what needed to be done to prevent that from happening again. Yet, two years ago, I received Nazi propagation in the mail in Pennsylvania. Last year, I witnessed people who I had respected – decent, caring people – defending our government putting children in cages.

S21 left me with a deep, empty sadness. I don’t have an action plan. I don’t know what needs to be done to prevent what happened at S21 from happening again. It’s not that simple. By most accounts, life in Cambodia under Norodom Sihanouk in the 1960s was good provided you weren’t a political rival and didn’t live along the Ho Chi Minh trail. Less than a decade later the nation descended into darkness. There’s a popular mantra going around that “we have so much more in common than what separates us.” I’m still mourning what Cambodia showed me about humanity and it’s capacity for cruelty not just to the ‘other’ but also to those who have so much in common.

4 Comments Add yours